TYNDALE IN WORMS – by Dr. Herbert Samworth

After their effort to have the New Testament printed in Cologne was frustrated, William Tyndale and William Roye fled up the Rhine River to the city the Worms. Just five years before, Martin Luther had taken his noble stand for the Reformation in that very city.

Like much of William Tyndale’s life and deeds, there is a paucity of information about his activities. However, we can surmise that he continued on his work of translating the New Testament and made arrangements with Peter Schoeffer to have the work printed in his establishment.

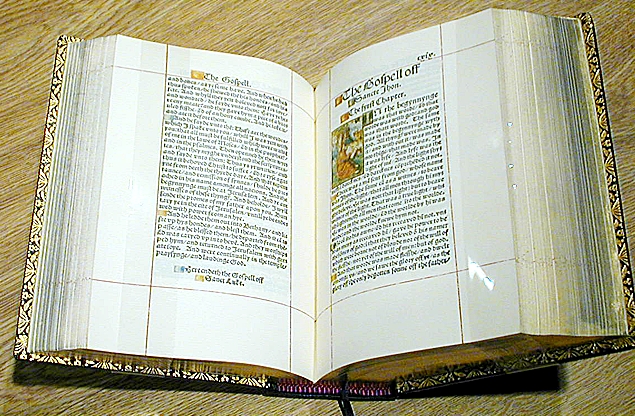

Finally, about March 1526 the New Testament was completed. It was the first printing of the complete New Testament in the English language. Unlike the Cologne fragment Tyndale did not add editorial notes. Basically it was the Greek of the New Testament rendered into the English language. It was printed in a neat octavo in Gothic type. Even today it is quite easy to read and one can imagine the excitement of an Englishman reading the Word of God for the first time in his native language. The translation is accurate and lively.

There are a number of unanswered questions about this edition. One question concerns the fate of the initial printing of the New Testament that began in Cologne. It was in quarto as the lone surviving fragment indicates. Did Tyndale finish that edition and also have an edition printed in the octavo size? There are some who believe that is exactly what happened. They are convinced that the quarto New Testament was completed in three thousand copies and an octavo edition was also printed in the same number of copies. If this were true, then a total of six thousand copies of the New Testament were printed by Schoeffer.

However, most experts believe that Tyndale abandoned his plan to have the New Testament printed in quarto and switched to the octavo size. What may have been the reasons for the switch are impossible to determine at the present time. However, it is a know fact that the three surviving copies are octavo and only the Cologne fragment survives in the quarto size. The result would be that three thousand copies of the New Testament were printed, all in octavo.

Whatever may have been the actual case, there remained no uncertainty that the printed English New Testament was still an illegal book under the Constitutions of Oxford. It was necessary that the New Testaments be smuggled into England. In this situation, Tyndale had the assistance of the Merchant Adventurers. The New Testament, either bound on unbound, would be hidden in barrels of flour or included in containers of cloth. Markings would be placed on the containers that indicated they contained Bibles.

The containers would then be shipped down the Rhine River, across the English Channel, and up the Thames River to the port of London. There they would be unloaded at a pier that was located next to the Steel Yard. It was here that all goods coming from Germany entered England. After the customs officials made their inspections, the workers at the Steel Yard, who were aware that New Testaments were on the way, would unpack the containers that held them, give them to Bible colporteurs who would sell them to those interested in securing a copy of the New Testament.

From our time in history, it is nearly impossible to grasp the interest people had in securing a copy of the New Testament. As soon as a shipment would arrive from Germany, it would quickly be distributed to the people.

However, the workers at the Steel Yard were not the only ones who were aware of the New Testaments due in England. Word had reached Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London, that a supply could be expected in late May or early June 1526. Tunstall organized his spies to intercept the shipments. It quickly became a race to get the New Testaments into the Steel Yard, distribute them to the colporteurs to have them sold or else have Tunstall’s minions intercept them. While a number of New Testaments made it safely into the hands of the public, it is also true that a goodly number were confiscated.

Finally in October of the same year, Cuthbert Tunstall and his spies had intercepted and confiscated a large supply of the Tyndale New Testaments. Tunstall decided to celebrate his successful venture by holding a special service at Saint Paul’s Cross in London. Tunstall was the featured preacher on the occasion and preached a sermon on why it is not necessary to have the Bible in English translation. He is reported to have held up a confiscated copy of the New Testament and roundly declared that it was a “strange” book with over two thousand translation errors. Following his sermon, Tunstall ordered that the New Testaments be burned. How many were consigned to the flames is unknown but this was the response of the English Church and clergy to the work of Tyndale in his attempt to give the English speaking people the Word of God in their native language.

How long Tyndale remained in Worms is impossible to state with accuracy. His next place of known residence was Antwerp in the Low Countries. However, it is not until the year 1529 or early 1530 that we can locate him there with confidence. Where was he and what did he do in the interval between his time in Worms and his residence in Antwerp?

Most Tyndale scholars believe that he resided for a short time in Antwerp and when he found that it was too dangerous to remain there, he returned to the city of Hamburg where he had resided before he went to Wittenberg and Cologne. There he took up residence again with Mrs. Emerson and continued his work of translation. However, there is no additional information concerning these events.

There is good reason to believe that following the printing of the New Testament, Tyndale turned his interests to the translation of the Old Testament. We can only speculate how he learned the Hebrew language, whether by his own study or at Wittenberg under Luther and Melanchton as we noted before. Apparently, Tyndale had translated a good portion of the books of Moses before he embarked on his voyage to Hamburg. On the voyage, the vessel on which he was sailing, suffered shipwreck and all Tyndale’s books and the translation that he had completed were lost. If this is true, it would have been a major setback to his attempt to translate the Bible into English.

However, what may appear to have been a discouragement to us would only impel Tyndale to persevere more in his desire to have the ploughboy know more the of Scripture than the priests of the Church of England.

Regardless of whether or not, Tyndale even went to Hamburg again and whether or not he did suffer shipwreck with the loss of his translations, the latter part of the year 1529 or early 1530 found him once again in Antwerp ready to have the first five books of the Bible printed in the English language. We will resume our story of Tyndale when he had the books of Moses printed in 1530.

Next: The Life of William Tyndale – Part 7: Tyndale and his Tracts